After the Clean Slate Act (S1553C/A6399B) was left out of the FY2023 budget, the Senate Codes Committee narrowly passed the bill on April 25, by a vote of 7-6, sending it to the Finance Committee for further consideration. It will be one of the more closely watched bills in the remainder of the legislative session.

The Clean Slate Act is sponsored by state Senator Zellnor Myrie, D-Brooklyn, Assembly Member Catalina Cruz, D-Queens, and is supported by New York’s largest employers like Verizon and JP Morgan Chase, along with the state’s largest labor unions. It’s also supported by New York City Mayor Eric Adams and local governments from Westchester to Buffalo.

The legislation was left out of the final budget agreement because Gov. Kathy Hochul could not come to an agreement with legislators over how long it should take for records to be sealed.

Passing the Clean Slate Act would make it easier for more than two million formerly incarcerated New Yorkers to access employment and stable housing by automatically sealing their conviction records upon release. This would expand on a 2017 law that allowed conviction records to be sealed “under certain conditions.”

The 2017 application-based sealing law was a sign of progress for Clean Slade advocates, but a Community Service Society report says that it “has proven ineffective at delivering the relief New York needs.” According to the report, “In the three years since it was enacted, less than [half of 1 percent] of the estimated eligible individuals have had their records cleared.”

The report continued by saying that the Clean Slate Act “provides automatic relief, to ensure that all eligible people benefit and that access to expungement does not depend on a person’s ability to afford legal counsel or navigate bureaucratic hurdles.”

The Clean Slate Coalition says the law passed in 2017 has been a failure because “far too few people know how to apply or have the resources to do so.” According to the coalition, “an estimated 600,000 New Yorkers are eligible to apply for records sealing under this law, fewer than 2,500 — less than 1 percent — have actually made it through the complex, burdensome process.”

Even after they complete their sentences, individuals with conviction records face rampant discrimination in the job and housing markets because employers are less likely to hire someone with a conviction record. Data shows that roughly 80 percent of individuals with conviction records in New York are Black or Latino. As a result, the current system has excluded 2.3 million New Yorkers — many of whom are Black or Latino — from accessing employment, housing, education, and other basic life essentials. This results in higher recidivism rates in these communities.

The largest contributing factors to recidivism include being unable to access housing, employment, or education after serving jail or prison time. This pushes people back into a position to be incarcerated repeatedly by forcing them into homelessness or criminal activity. Automatically sealing criminal records could reduce recidivism by eliminating some systemic barriers that prevent formerly incarcerated people from accessing stable housing and employment.

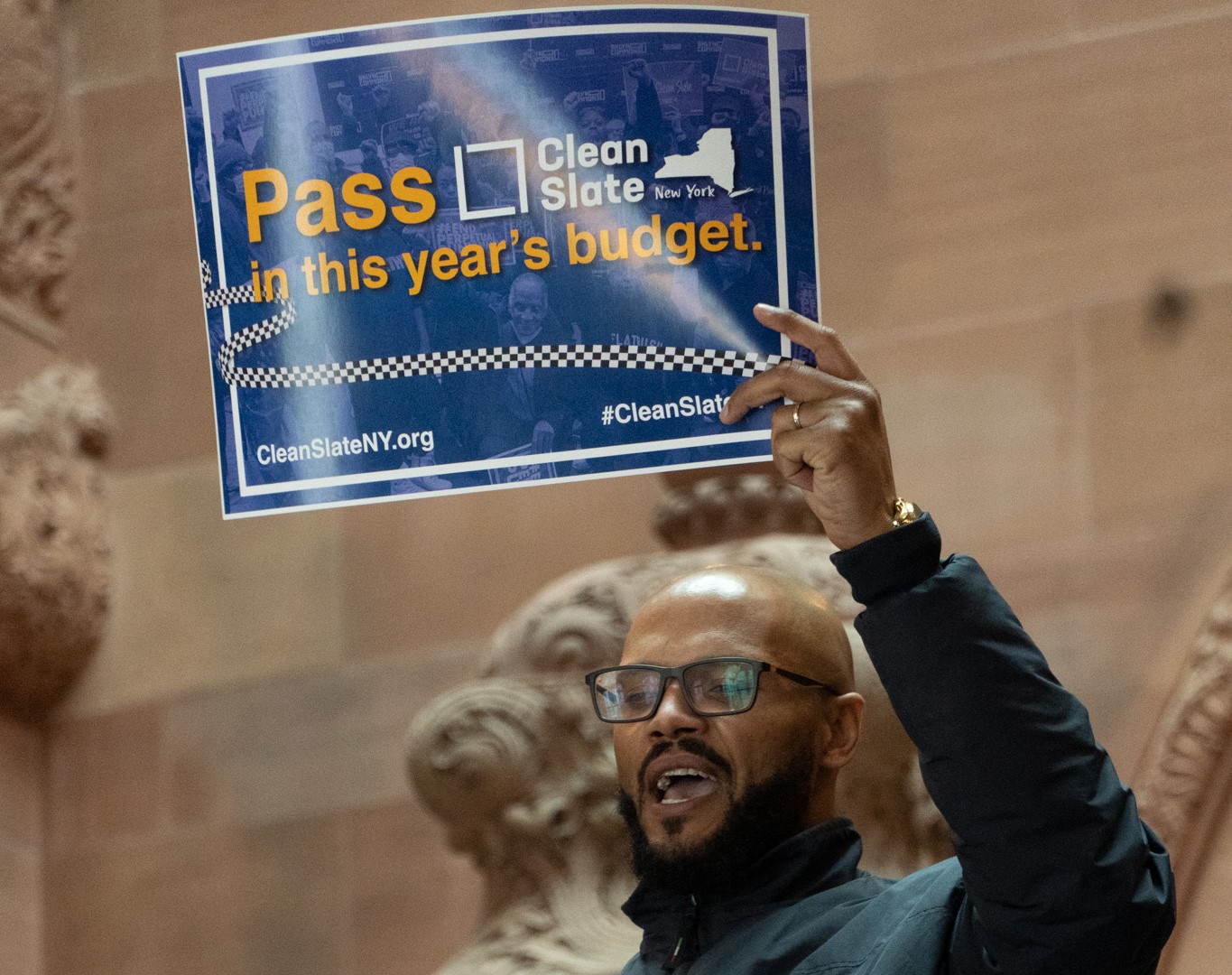

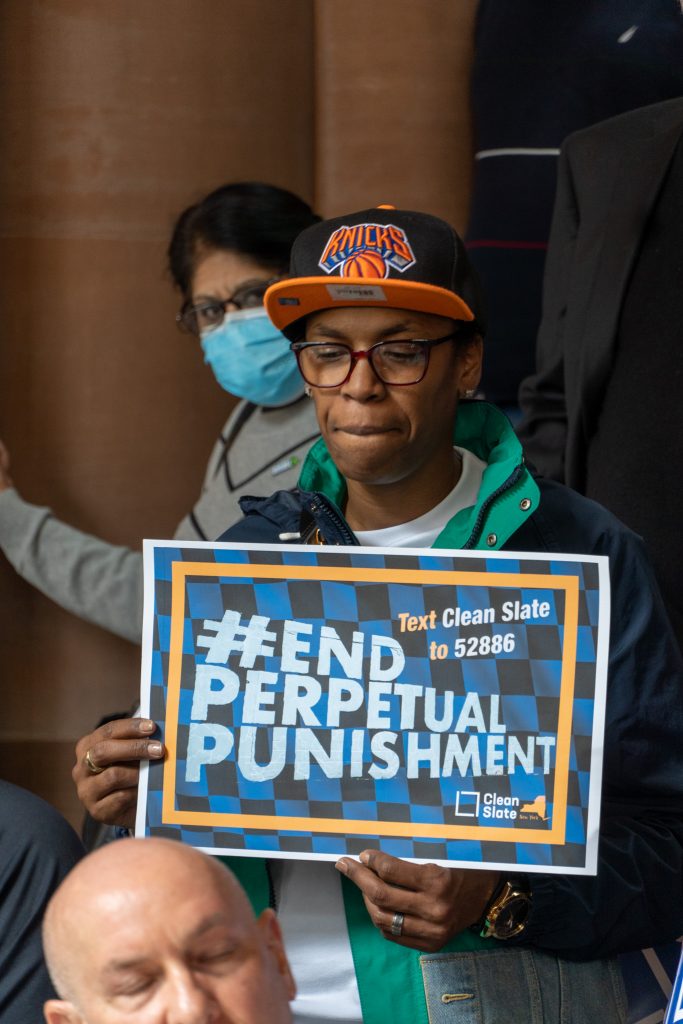

Before the final budget was passed, supporters of the Clean Slate bill held a large rally at the Capitol on March 23 in a final attempt to pressure the governor into including Clean Slate in the budget.

During the event, David Delancy, who was incarcerated at the age of 17, explained how the current system has made it harder for him to access stable housing for his family. According to Delancy, after he lost housing last year he went to more than 40 interviews and was turned down after the background check each time.

“I filled out 40 applications, spent $90 each time just to be told no because of something that happened when I was a kid,” he said. Delancy explained that the Clean Slate Act is not “a bill that is gonna let people commit crimes. We’re talking about a bill that is gonna give people a chance to use resources to enhance their life.”

Advocates of the Clean Slate Act also say that passing it will improve New York’s economy and help break the cycle of generational poverty experienced by millions of formerly incarcerated New Yorkers and their families.

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) has estimated that using background checks and other barriers to exclude people with conviction records from employment opportunities “costs the economy between $78 billion and $87 billion in lost domestic product.” The Clean Slate coalition has also said that excluding formerly incarcerated people from the workforce “costs New York nearly $2 billion in lost wages annually.”

Gov. Hochul pledged to support the Clean Slate Act during her State of the State Address by promising to include a provision in next fiscal year’s budget that would prohibit landlords from automatically denying housing to people based on conviction records. However, advocates of the Clean Slate Act say that the governor’s version of the bill contained loopholes that would allow landlords to continue to reject tenants based on conviction records.

During the rally, Assembly Member Catalina Cruz, D-Queens, explained that another difference between the legislature’s version of Clean Slate and the governor’s version of the bill is that “Under the Governors version someone could be waiting 22 years to actually be able to have their record sealed, while in our version its seven years for felonies and three years for misdemeanors.”

This is because the waiting period in the Legislature’s version starts from the day a person is released from jail or prison, whereas the waiting period doesn’t begin until the “maximum hypothetical expiration of incarceration” in the executive proposal. That includes probation which adds years to the waiting period.

The Legislature’s version of the bill also ensures enforcement of Clean Slate by amending Human Rights Law to prohibit employers from considering sealed records. It also allows individuals to sue employers for violating the sealing law. There are no such enforcement mechanisms in the governor’s version that passed in the budget.

A Clean Slate coalition report explained that while the governor’s support of the Clean Slate Act is “an important step forward”, the version of the bill in the proposed budget “would significantly weaken the existing bill, including dramatically delaying when an individual becomes eligible for sealing, which would prevent them from moving forward with their lives.”

“We are in a society that says we are progressive and that we’re gonna move forward and give people second chances and that starts right now with this legislative bill,” Delancy said. “There is no reason for the Clean Slate Act not to pass except for our own little fears.”